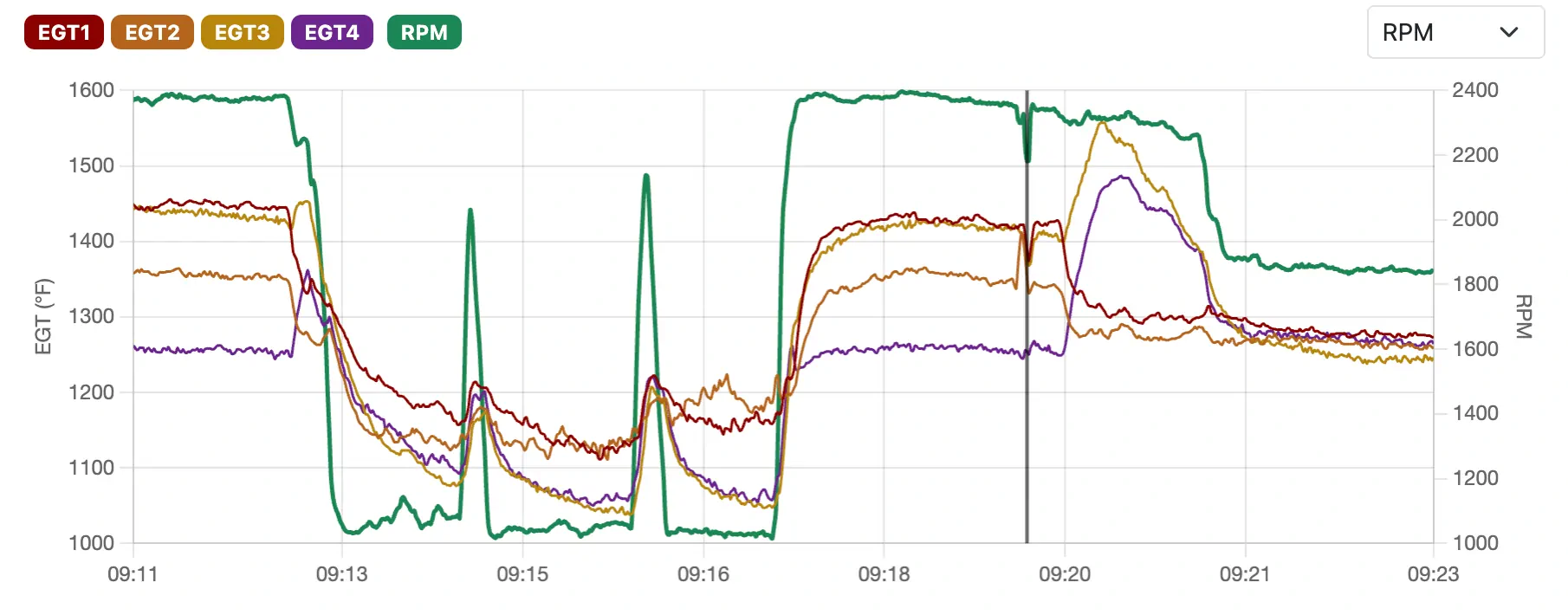

Tom had been out practicing for his commercial checkride. He'd been doing steep spirals at 75 knots, carb heat on. Leveled off, pushed it in, started climbing. Then the engine burbled.

The data told us exactly what happened.

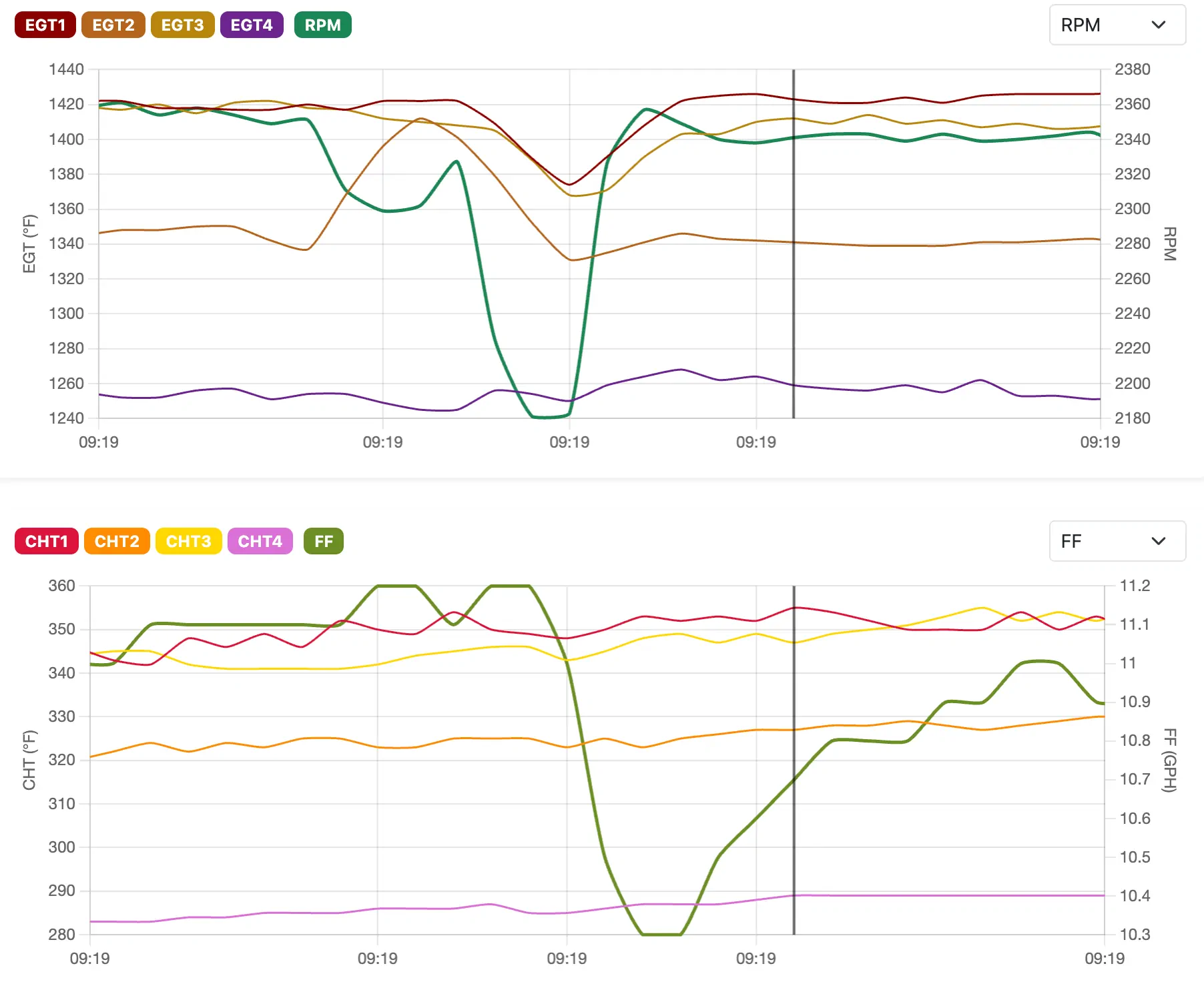

During the spirals, CHTs fell to 250°F (121°C). The engine was cold. Carb heat was doing its job.

Then he pushed it in.

RPM drops. Fuel flow lags slightly behind. That's an ice chunk breaking loose—restricting airflow, richening the mixture, killing power.

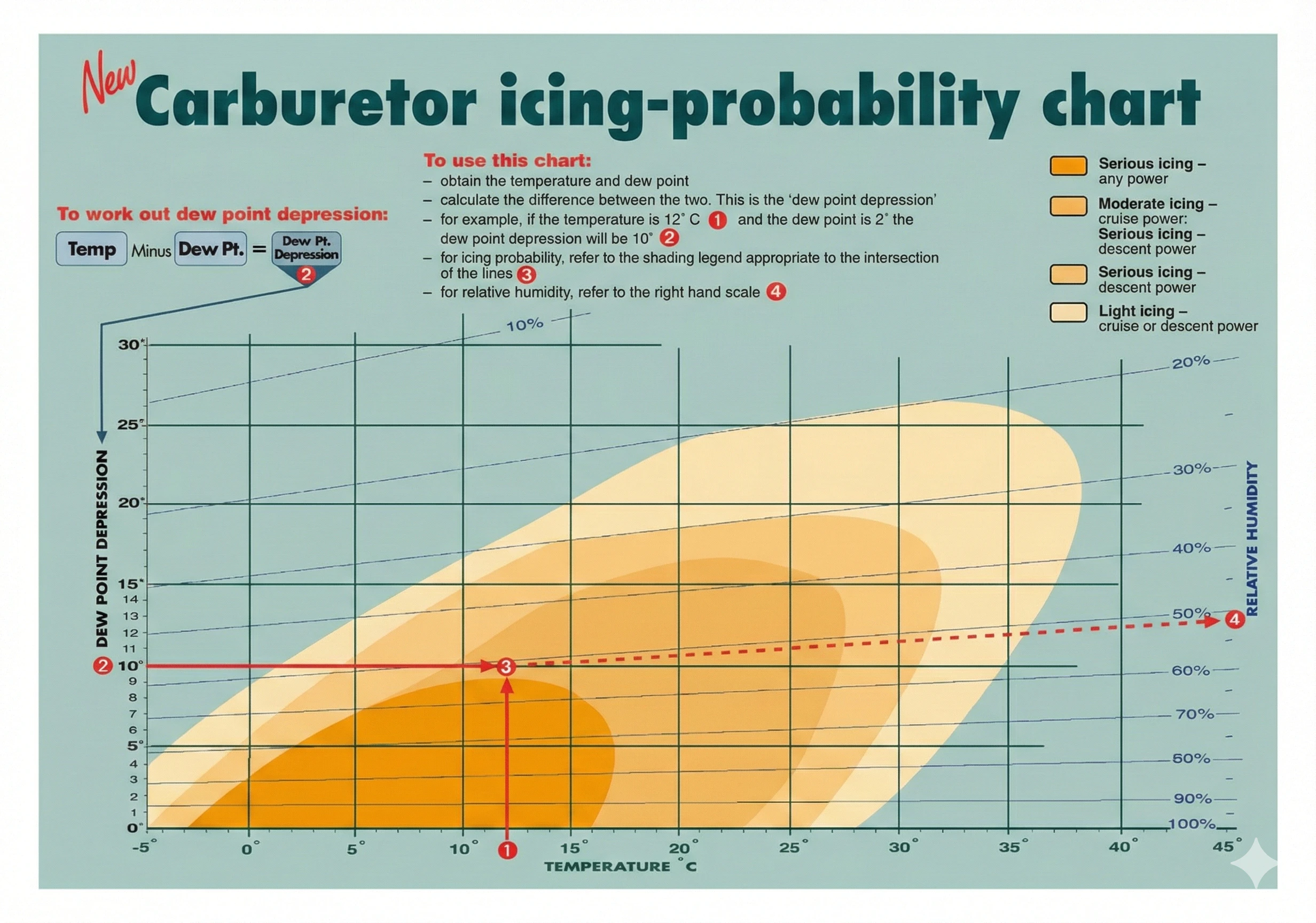

I pulled the weather: 53°F (12°C), 46°F (8°C) dewpoint, 76% humidity. Dead center of the Carburetor Icing Probability Chart's "Serious Icing" zone.

Source: NTSB

The Sequence

- Carb heat ON during spirals → ice prevented

- Returns to cruise, pushes carb heat IN → cold air now flowing through a cold carburetor

- Moderate power (~2,300 RPM)—not enough heat to self-protect

- Two minutes of accumulation in prime icing conditions

- Ice chunk restricts airflow, causes momentary power loss

The mistake: Carb heat protected him during the maneuver. Pushing it in removed that protection while the carb was still cold and conditions were still prime.

The Fix

Leave carb heat on for another minute or two after returning to cruise. Let everything warm up before you remove the protection.

Lycoming's service instruction on carb heat makes it clear: moderate power in marginal conditions is often the most dangerous zone, because the engine isn't making enough heat to protect itself.

Tom flies smarter about carb heat now. The data made it obvious.